Jonathan Moore’s 2019 photo essay ZAETA is the story of a community of refugees living in the remains of a world that ended decades ago. In the early 1990s a conflict in Abkhazia - a disputed territory on the western edge of Georgia - caused around 200,000 people to be displaced. Around 10,000 of them were placed in the remains of an extravagant network of hotels built by Stalin as a symbol of Soviet prosperity, at a time when citizens were required to take enforced rest.

An online exhibition by Albumen Gallery with around 40-50 images from the series ZAETA will open on August 6th and will run until October 2nd. Albumen Gallery is a London based Fine Art Photography Dealer and Gallery Project.

Zaeta (3) by Jonathan Moore

Zaeta

Commitment, willingness to take risks, and operating without 'a safety net' are crucial factors in Jonathan Moore's projects - essential for achieving the directness, truthfulness, and emotional impact his images convey - nowhere more so than in Zaeta.

Jonathan Moore’s 2019 photo essay Zaeta is the story of a community of refugees living in the remains of a world that ended decades ago. In the early 1990s a conflict in Abkhazia - a disputed territory on the western edge of Georgia - caused around 200,000 people to be displaced. Around 10,000 of them were placed in the remains of an extravagant network of hotels built by Stalin as a symbol of Soviet prosperity, at a time when citizens were required to take enforced rest. Nearly 30 years later, several hundred refugees remain, and the hotels have become a permanent home to multiple generations. Amid these crumbling remnants of once decadent surroundings from another time, the refugees have built their lives in a post-apocalyptic environment despite their struggle for necessities.

Zaeta (2) by Jonathan Moore

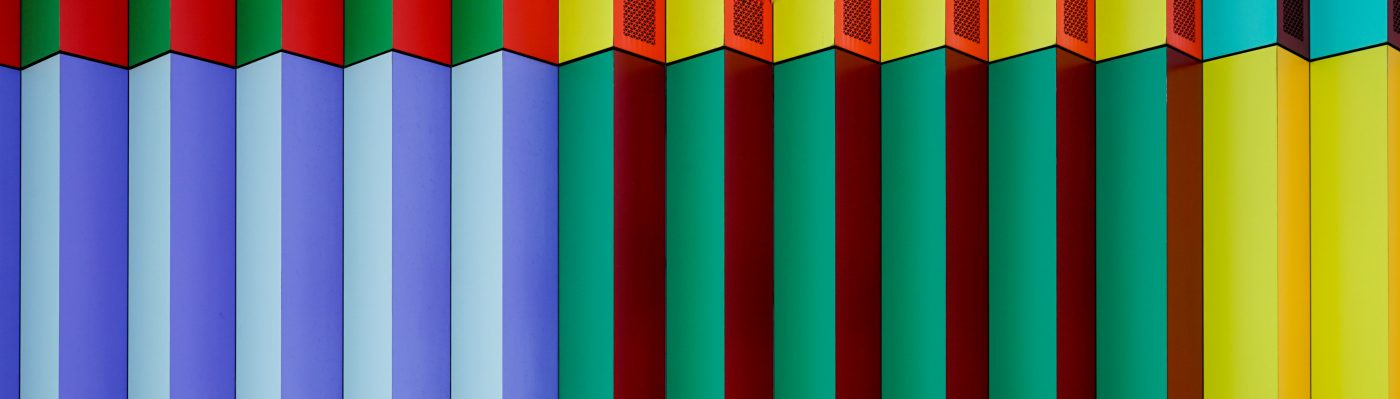

In the early 1990s a conflict in Abkhazia - a disputed territory on the western edge of Georgia - caused around 200,000 people to be displaced. Around 10,000 of them were placed in the remains of an extravagant network of hotels built by Stalin as a symbol of Soviet prosperity, at a time when citizens were required to take enforced rest

Not unusual for Jonathan Moore's work, from the outset the project chartered its course defying any proactive and prior planning. - "A big part of the attraction of trips and projects like this for me is that you never know exactly what you’re going to find." - He had originally planned to visit Abkhazia, a disputed territory on the western edge of Georgia that had been at war with the country in the early 1990s, but the border was closed just a few days before he was due to leave. Forced to reassess he found reference to a group of derelict hotels where people who were displaced from Abkhazia by the war lived. Jonathan Moore recalls: "The architecture of the hotels featured prominently in the articles I found, but the people in them were either ignored completely or referred to at the end with advice to leave them alone because they are vulnerable. I understand where this comes from, but believe it’s possible to photograph people in any situation with the right approach, consent, and involvement, and that it’s important for photography not to turn away from in situations like this." He decided to use the week he had in Georgia to try and meet the people there and begin telling their stories.

Zaeta (10) by Jonathan Moore

"The architecture of the hotels featured prominently in the articles I found, but the people in them were either ignored completely or referred to at the end with advice to leave them alone because they are vulnerable."

Whilst not without risks, the fact that he had set out for what resulted in Zaeta on his own proved to be an advantage. "For the vast majority, I work alone. Particularly when you’re an outsider, or in a sensitive area, so much depends on the relationships you’re able to build. That dynamic is delicate and shifts considerably when other people are involved and I believe it’s harder, or at least much more complicated, to do that successfully if you’re not alone."

The hotels where the refugees live were built during the Stalinist era. In their pomp, they would have been a grand statement of Soviet power and success. There are 25 / 30 hotels, some that would have slept 100s of people and others quite small, built around a hill and set back from the road, with an enormous public park running along one edge and snow-capped mountains on three sides. Once the area would have been full of life but today it is a relic of that time.

The hotels are now literally rusting and falling apart. The place is so still and its aura and aesthetic are post-apocalyptic. You could easily drive past without noticing signs of life but when you get closer you can see washing hanging on the balconies of the upper floors of the hotels.

The project is named Zaeta because it’s a local slang word that means ‘together’ that a friend I made there used to describe the attitudes of the refugees towards one another.

Zaeta (7) by Jonathan Moore

The hotels where the refugees live were built during the Stalinist era. In their pomp, they would have been a grand statement of Soviet power and success. There are 25 / 30 hotels, some that would have slept 100s of people and others quite small, built around a hill and set back from the road, with an enormous public park running along one edge and snow-capped mountains on three sides. Once the area would have been full of life but today it is a relic of that time.

Click on one image to open the gallery

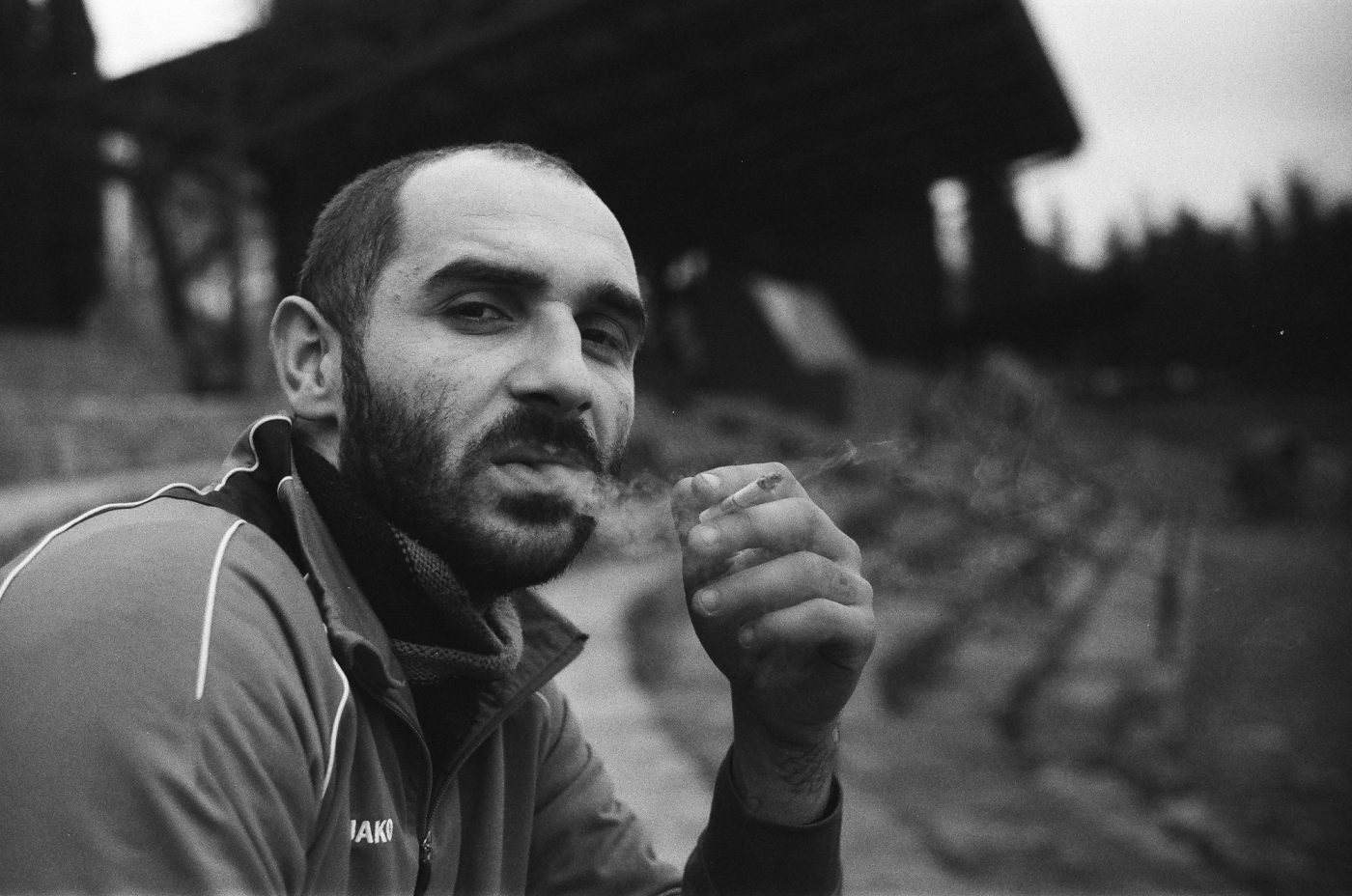

"We talked briefly, but I didn’t get a good feeling from him. Murtazi then came down one of the open staircases with an ax in his hand, tattoos on his neck and hands, looking quite intimidating but smiling broadly. I was immediately drawn to him. He ran off and came back with a camera and pointed to the roof. I followed him there and we spent the day eating bread and meat and drinking homemade wine."

Murtazi

“Murtazi had maybe 50 or 100 words in English. I know more about him that I can explain. We used hand gestures, drew on the floor of the hotels in broken brick, reading body language. We just understood each other. I realize how that sounds but it’s true.“

Jonathan Moore on meeting Murtazi

I got a bus from the town I was staying into the hotels and could them on the hill. I walked towards one of them and didn’t have my camera out at this stage. I could see signs of life on the upper floors. I went into what once would have been the reception of the hotel and there was rubble everywhere. The first person I saw was an elderly lady. I smiled and waved and she shouted up to the upper floors. At that point, I didn’t know what would happen but a guy down to talk to me who spoke English.

We talked briefly, but I didn’t get a good feeling from him. Murtazi then came down one of the open staircases with an ax in his hand, tattoos on his neck and hands, looking quite intimidating but smiling broadly. I was immediately drawn to him. He ran off and came back with a camera and pointed to the roof. I followed him there and we spent the day eating bread and meat and drinking homemade wine.

I felt incredibly lucky but still kept my wits about despite the amount we drank, but it hit me all at once later that night. All of a sudden I could barely stand. I have vague memories of being helped down the stairs and into a taxi, but the next thing I knew I was back in my hotel the following morning. I was too hungover to even check that my cameras were in my bag until the evening and was too sick to go back to the hotel's until the following day.

I got there and found out that Murtazi had spent the previous day going around all the hotels he could think of trying to find me because he was worried the taxi driver had kidnapped me. This, and the fact that he and the people there could have taken everything I had and left me in a ditch, made me realize I had found something and someone very special.

Other than the one person I met at first, nobody I met could speak English. Murtazi had maybe 50 or 100 words in English. I know more about him that I can explain. We used hand gestures, drew on the floor of the hotels in broken brick, reading body language. We just understood each other. I realize how that sounds but it’s true.

You lose a lot from not being able to speak the same language as people you meet but you gain a lot too. I think it allows you to blend into the background more, a degree of invisibility, and can make people more comfortable and natural around you. I think you get a different type of photograph.

Jonathan Moore, Photo by Murtazi

The first principle of reportage documentary photography for Jonathan Moor is that the work needs to be honest.

In a relatively short time, Jonathan Moore has established himself as a documentary photographer to watch. The story of how he became a professional photographer is interesting and insightful for understanding his photography. A line can be drawn between his pre-photography years and dedicated his life to documentary photography. Before picking up a camera Jonathan Moore spent most of his adult life in the world of politics and campaigning. Following years working in a variety of political advisory roles and in the government more recently he had a policy role for a mental health charity.

Yet his photography did not become a mere vehicle to drive & push certain tactical issues or campaigns. In his hands, the camera serves a purer purpose. In the first instance, he aims through his images to create a lasting visual memory.

From the age of 18 traveling and particularly traveling to quite outlandish places had been an important part of his life - driven by a pang of hunger and desire to understand more about the world. Attempts of writing to capture and distilling what he experienced usually ended in frustration.

He discovered photography when in preparation for a trip to Bangladesh he bought a camera. Before using cameras, he says "I used to remember things that taught me something, made me feel something, or struck me as significant. Those memories are now the photographs that I take." Jonathan Moore's documentary photography is visual memory, which under the medium is shared with a wider audience.

The first principle of reportage documentary photography for Jonathan Moor is that the work needs to be honest. Only this honesty will allow photography to be an agent for dispelling myths or misled beliefs and raise the profile of things that otherwise might be hidden, and ultimately tell the truth.

In the early days of his photography capturing what he photographed was important for recording his understanding of what he saw and experienced. With a growing body of work and as his reputation grows, there is a mission for his photography to play a role beyond the merely personal visual memory - to highlight issues, to inform, and to help the people he comes across who find themselves in difficult circumstances.

Albumen Gallery

The online exhibition ZAETA open on August 6th and will run until October 2nd. Albumen Gallery is a London based Fine Art Photography Dealer and Gallery Project. It was set up to provide through its online gallery space an international platform for original photographic art. From its inception, Albumen Gallery has been pioneering and expanding the online exhibition medium. The regular programme of curated online exhibitions is internationally recognised for their accessibility and artistic interest. Their advisory service is tailored to the requirements of lovers of Fine Art Photography and collectors who seek a trustworthy partner for growing their collection.

Journalism and running an online magazine costs money. Our online magazine is free of advertisements – we finance our costs exclusively from donations. It is unlikely that we will become rich in this way, but that is not our intention either. We do everything out of love and dedication. We are not profit oriented. Support Tagree so that the magazine remains ad-free and the monthly costs can be paid. Yes TAGREE, I love the cultural work you do, I donate to show you my sincere appreciation: